* Disclaimer: Maddy, Grace, Bella and Molly are fake names that are used to protect the anonymity of several student-athletes mentioned in this piece

Every morning, Meredith Rose would wake up at dawn to run between six and ten miles. She would walk quietly on her tippy-toes, making sure not to awaken her roommate and further fuel her suspicion that something was going on. After her daily run, Meredith would shower and head to the student center for a nutrition-filled breakfast: a rice cake and a banana.

“Cause that’s how you fuel yourself after a 10-mile run,” laughs Meredith sarcastically. A 10-mile run burns almost 1,000 calories, yet her rice cake and banana duo has a mere 140 calories. Meredith would head to class, then back to Dana to get a piece of grilled chicken and salad for lunch. Her fear food was carbs, so she would avoid anything in that food group to appease her disorder.

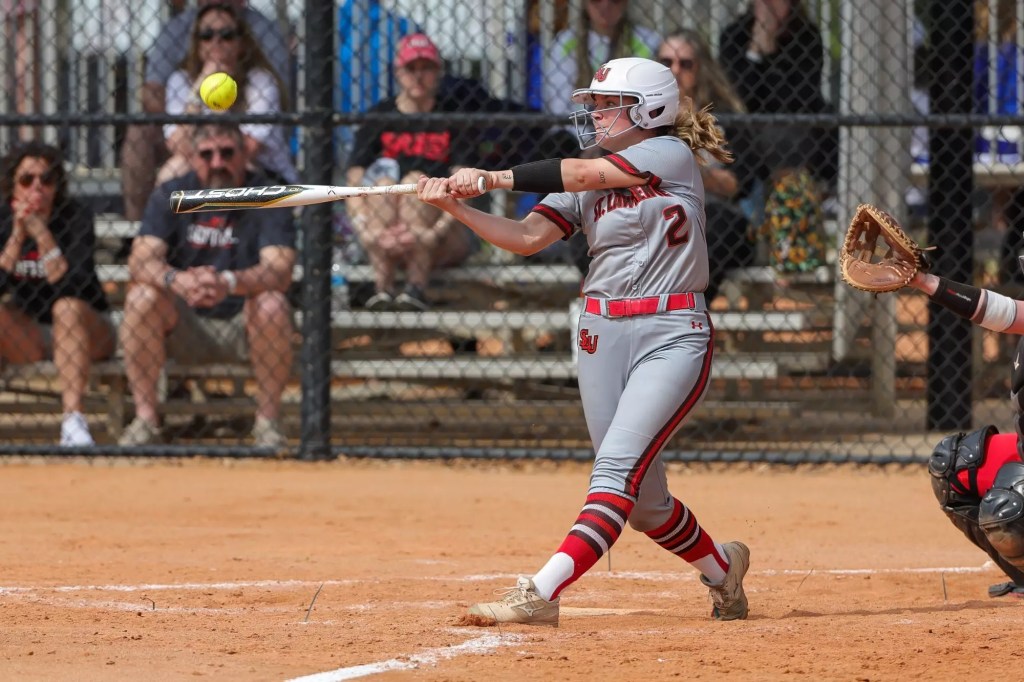

Meredith, a member of the St. Lawrence softball team, struggled with a severe eating disorder during her sophomore year of college. Her routine and caloric intake would be insufficient and dangerous for anyone, but especially an NCAA athlete.

Meredith would go to a two-hour softball practice after class, which was sometimes accompanied by a lift for another hour. Her three hours of practice and 10-mile run were all done without eating any carbs, which forced her body to break down her own muscle tissue for fuel. After practice, Meredith would go back to Dana to eat grilled chicken and salad again.

“Then for dessert, if I did have a dessert, it was an apple,” says Meredith.

Typical of eating disorders, Meredith forced herself to follow a rigid routine of exercise, restriction, and food rituals. She would make herself wait at least four hours after eating to have more food, regardless of her hunger level or appetite. If Meredith broke the routine, her eating disorder would find ways to compensate for the extra calories.

“If I did cheat, I either took a lot of laxatives or I would try to make myself throw up,” says Meredith. “But yeah, that would be like a typical day in the life I’d say.” Despite her efforts to break out of this destructive cycle, Meredith’s eating disorder kept her prisoner to its grasp.

I fell victim to a similar cycle as Meredith during my sophomore year at boarding school. I was a tri-varsity athlete, and my eating disorder began as a way to get in shape and do better athletically. What started as skipping dessert and going for runs quickly escalated into skipping two meals a day and doing workouts in my room before I was allowed to go to bed. Similarly to Meredith, I would compensate after eating something unhealthy. I would make myself throw up in the basement of my dorm, desperate to keep my eating disorder a secret.

Starving myself and throwing up inevitably started to negatively affect my performance. I started losing muscle, had no energy to play, and was forced to sit out of practice due to dizziness. The lack of nutrition and exercise volume also led to a stress fracture in my foot during squash season in the winter. Being injured further escalated my behavior use, and I started waking up at 5 a.m. to go to free swim, before cycling for an hour and a half in the afternoon. I was no longer working out to improve my athletic performance; I was doing it to be as thin as possible.

My eating disorder thrived living away from home with less supervision and monitoring of my food. I have been in recovery for four years now, but admit that the college environment still triggers me at times. Although I did not suffer from an active eating disorder as a student-athlete, I have always been curious about how certain elements of collegiate athletics might exacerbate disordered behaviors.

Female athletes are estimated to have disordered eating rates around 62 percent, according to Aram Gomez, the Athletic Counselor at the St. Lawrence Health and Counseling Services.

Meredith admits that softball is not a sport that necessarily places athletes at a high risk of developing an eating disorder. However, she did find that indirect elements of being on a college team escalated her behaviors, such as teammates complimenting her body after losing weight and struggling with societal expectations of what a female athlete’s body should look like.

My sports in high school – lacrosse, squash and soccer – did not cause my eating disorder either. Rather, it was the stress of being an athlete in a highly competitive environment that fueled my behaviors.

“I think any student-athlete could be at risk,” says Assistant Athletic Director and Head Athletic Trainer Brian Atkins. “It just depends on their history of things, because it’s not just a sport-related disease – it’s life and what else might be going on in their lives along with it.”

While any athlete can have an eating disorder, sports that emphasize thinness in connection to improved athletic performance have an increased risk of leading to disordered eating behaviors.

Gomez says that performance expectations and emphasis on body shape can create toxic situations for student-athletes that place them at a higher risk of developing an eating disorder. Running is a sport that often emphasizes a thin-to-win mentality.

Maddy is a senior on the cross-country and track teams at St. Lawrence. She developed an eating disorder in high school and has been in recovery for several years. Her lived experience has given her insight into the harmful misconceptions around weight and athletic performance in cross country and track.

“I think in running there’s just this connotation that to be fast you have to be really very thin,” says Maddy. “And you get in the mindset that you don’t need to fuel yourself to run fast because some of the fastest runners are extremely thin.”

Grace is a former member of the track team at St. Lawrence. She found herself developing disordered eating habits the summer before coming to SLU, and being a student-athlete in the college environment escalated these behaviors. She was diagnosed with an eating disorder during her first season. She fell into the harmful thought pattern that she had to be skinnier to improve her times and performance ability.

“I think it’s believed that if you’re a lighter weight, you’ll be able to run faster,” says Grace. “This isn’t necessarily true, because obviously if you don’t have enough energy you won’t be able to run faster.”

“On a sports team at a university, a lot of girls want to control a lot of things, and you think that you can control how much you’re eating and how much you’re putting into your body, and that will help you be a better runner,” says Maddy. “But something I learned is that that’s not the case, fuel is fire.”

My eating disorder disguised itself as an attempt to eat cleaner to do better in sports. In reality, it was a way to feel like I was in control as a new student in the high-pressure environment of boarding school.

I had always believed being thinner correlated with being more successful in sports, and I reasoned that losing weight was the missing piece I needed to do better at sports, as well as find the perfect friend group, get good grades, be popular, and make my crush like me back. However, what I thought would be the magical solution to my problems ended up being the force that made my life fall apart.

“Our society considers being fit as being skinny,” says Meredith. “It’s hard to escape that stereotype, especially as a woman.”

I believed this stereotype growing up. When I started playing worse during my sophomore soccer season I immediately blamed my weight. I failed to consider that the reason for the change was that I was actually not eating enough. My mind could not seem to fathom that I could ever be a better version of myself in a larger body.

“I do think that some student-athletes tend to think that if they weigh less they will perform better,” says Atkins. He has noticed that endurance athletes, such as runners and swimmers, tend to be more at risk for developing disordered eating behaviors due to the intensity level and necessity for high caloric intake.

Misconceptions surrounding weight and running ability can lead to women trying to drop weight to fit the societal expectation of what a fast runner’s body must look like.

“With running there’s a body type that people seem to think is what a runner should look like and it’s usually very skinny, very thin, and just very toned,” adds Grace. “I think there is a lot of drive for girls that think they should look like that to be a good runner.”

“It’s so easy to be consumed by the mindset of reaching a certain goal or leaning into the stigma of being a female runner,” Maddy says. “At the end of the day, anyone can run – any body type – and that’s what makes running so cool.”

Running is not exclusive to stick-thin athletes, and Maddy wishes that more people could let themselves run without feeling a need to fit their body size into the stereotypical mold of a cross-country or track athlete.

Endurance athletes also strive to minimize drag, which is defined as having any extra fabric on their uniforms that can slow them down. As a result, these sports tend to have form-fitting uniforms that cover minimal skin and can cause body image distress.

“Endurance athletes can have uniforms that don’t cover as much, like a diving or swimming athlete,” says Atkins. “All they’re wearing is a swimsuit so they become very self-conscious about their appearance, and can take a very unhealthy approach to eating to make sure they look a certain way in it.”

“Wearing a bathing suit for hours each day could exacerbate body image issues,” says Molly, a junior on the swim team at SLU. “I know of several people that I have swam with in the past who struggle with disordered eating that is more prevalent during the season than out of season.”

Bella is a former member of the St. Lawrence volleyball team. While she did not struggle herself, Bella noticed some teammates were overly careful about what they ate and did not eat enough to properly sustain the activity level of being a college athlete.

“There were some points where I thought to myself ‘how are they getting through tough workouts and days while eating so little?’” Bella says.

Volleyball uniforms can also cause body-image issues due to the tight spandex the girls wear. In my experience, just wearing lacrosse shorts has been a trigger for me because I feel insecure about how chubby my legs are and compare how my teammates’ thighs look thinner than mine. My recovery journey has taught me not to act on these negative thoughts, but I can’t help but think that being thinner would make me a better player.

“I think with being a female athlete and seeing other female athletes around the athletic center, a lot of body comparison happens in my head,” says Meredith. “I think there is a certain level of expectation about how you should look that comes with being a female athlete.”

Meredith could engage in eating disorder behaviors more secretly in the fall without repercussions, but being in season in the spring revealed the negative impact her eating disorder had on her athletic performance. So many athletes believe they will be better at their sport if they are thinner, but Meredith quickly realized how false this was.

“I had lost so much weight my sophomore season that I lost my starting spot,” says Meredith.

In April of her sophomore year, Meredith hit rock bottom when she overdosed on laxatives the night before one of her softball games.

“I was up all night throwing up and there was blood in my throw-up,” says Meredith. “But I was too scared to tell anybody because I didn’t want to go to the hospital, and we had a game the next day.” Despite the extreme side effects of her laxative abuse, Meredith refused to miss her game.

“During warm-ups, I ended up over a trash can just dry heaving because I was so sick,” says Meredith. “When you overdose on laxatives that’s usually what happens. I had to get rushed to the hospital in an ambulance in front of my whole team.”

At the hospital, Meredith had emergency laparoscopic surgery to fix her intestines, which had become twisted together as a result of her laxative abuse. Meredith’s surgeon told her that if she had gone home and taken more laxatives she probably would not have woken up the next morning.

“I think that was kind of my point of like, ‘okay if I need to change, it needs to be now or I’m going to die,’” says Meredith. Almost dying at her game was an eye-opening moment to the true dangers of her eating disorder. Meredith knew she had no other choice but to recover.

Meredith barely played in the last few games of the season because her coach knew she was not strong enough.

Framed pictures of past teams line the walls of Atkins’ office in the corner of the training room. Athletic trainers, like Atkins, play a key role in the treatment of eating disorders in student-athletes.

“Sometimes they [athletic trainers] could be the main person that’s a point of contact,” says Atkins. “The doctors are talking to the student-athlete, the counselor might be talking to the student-athlete, a nutritionist might be talking to the student-athlete, and the athletic trainer is trying to gauge all of that or get that information in to see the recovery process for a particular student-athlete.”

“Effective treatment will require identifying and starting to build a treatment team involving trainers, physicians, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and accommodations through the Dean’s Office,” Gomez says, echoing Atkins’ emphasis on building a treatment team to help support student-athletes.

Atkins also stresses the importance of treating each student-athlete on a case-by-case basis. Receiving an eating disorder diagnosis does not necessarily mean an athlete must stop playing their sport, but it does require frequent monitoring of vital signs and regular check-ins to ensure their body can sustain physical activity. Atkins recognizes the benefits that playing a sport can have on students, but also recognizes physical warning signs that might require some time off – such as a low heart rate, low blood pressure, and heart palpitations.

“The athlete’s health, physical and emotional safety, and self-image should all be considered in decisions regarding the level of participation for the athlete in their sport,” Gomez adds, highlighting his holistic approach in his work with athletes who struggle with eating disorders. He follows an empowerment model and strives to develop genuine trust with his patients, while also assessing physical and mental health safety concerns.

“We want to do whatever we can to make sure you’re as healthy as you can be for the sport you want to participate in,” Atkins says. “Sometimes that means not participating for a period of time, and sometimes that means participating, but the student-athletes need to be invested as well.”

“I was diagnosed when I was in season, so that was difficult because I had to work with the athletic trainers and with my coach because I didn’t want to stop running – I wanted to keep going,” Grace recalls. “But my doctors didn’t want me running the same amount of mileage that I was doing before, so I had to lower it by about 10-15 miles per week, which was challenging.” Grace dedicated herself to her recovery, eating all three meals plus snacks after being diagnosed. The high-intensity nature of track made it difficult for her to restore to her original weight, but Grace stabilized her weight and in turn got to continue running with a few modifications to accommodate her eating disorder.

However, not every athlete is as recovery-oriented and motivated as Grace was. Student-athletes who continue to engage in eating disorder behaviors without attempts at recovery are often sidelined by their trainer due to medical instability.

“That’s a really hard conversation because typically student-athletes don’t want to be told no,” Atkins says about the decision that an athlete’s physical health is too unstable to continue playing their sport. “They want to continue pushing forward because they think and they feel that’s the right thing to do.”

Ambivalence and the inability to fully buy into recovery makes the entire process more difficult. Working with one’s support team is a two-way street – an athlete must put in the work to recover to be successful, and their athletic trainer and mental health counselor will help them along the way. These members of their treatment team can guide them to the door, but ultimately the athlete is the only one who can open it and choose recovery for themselves.

Meredith did not know that athletic trainers could serve as a resource for her.

“I wasn’t injured or anything, so I kind of felt like I didn’t need to go to the trainer for that,” Meredith admits. “Looking back, I obviously regret that and wish I had gone to the trainer.”

Meredith returned to Canton in the fall of her junior year, excited to experience SLU again, but this time in recovery. By the time her season started in the spring, Meredith had been in recovery for almost a year and had a newfound gratitude for being able to play softball again.

“Quite honestly, I had the best season of my life my junior year, it just felt great to be back out there,” smiles Meredith.

Meredith’s yearly stats reflect her incredible talent on the softball diamond, as well the detrimental impact her eating disorder had on her performance. Her hitting average went from 0.324% her first year, to 0.190% her sophomore season, back up to 0.330% her junior year. She had 14 runs and 24 hits as a first-year, 9 runs and 11 hits as a sophomore, and 18 runs and 36 hits as a junior. Meredith’s junior season was even more impressive considering the obstacles she had to overcome to make it back on the field.

“It kind of changes your perspective,” says Meredith. “I wasn’t even upset if I did bad, I was more like ‘thank God I get to do bad.’”

At first, Meredith struggled to accept her healthy body. She would compare her roster photos, grieving the skinnier version of her face in the older one. Meredith also felt embarrassed needing to tell her coach that she needed a larger uniform size.

“I had to stop myself from thinking it was embarrassing and start thinking that it was normal,” Meredith says. “I should be a size medium.”

Meredith also learned how to set boundaries with friends to protect her recovery. Her biggest fear was having people comment on her body, specifically how it looked different from how it was when she was actively struggling with an eating disorder.

“It was about me having to be open and be like ‘hey I don’t want you to comment about my body’ and stuff like that,” Meredith says. “I didn’t ever say that my sophomore year, so it was good to be able to do that.”

Meredith recognized that she isolated herself during her eating disorder to help keep her struggles private.

“If I didn’t have to go out to dinner with my friends, then I didn’t have to not eat in front of them and it was just easier for me,” she says. In recovery, Meredith has learned to lean on her friends for support, rather than draw herself away from them.

“My biggest thing when I’m trying to keep myself on track is to be around people,” says Meredith. “I definitely hang out with my friends more.” The sound of nearby chatter echoes through the walls of her sorority house, a reminder of the love and friendship that she is surrounded by whenever she needs it.

Over half of female student-athletes struggle with disordered eating, yet the silent stigma of dealing with mental health conditions often results in athletes choosing to face their struggles alone.

Meredith wishes she had known a person in recovery that could have been a resource for her sophomore year. The loneliness she felt during her eating disorder is one of the reasons that Meredith is very open about her struggles now – she is the person her younger self wished she had. Meredith’s story is also a beacon of hope for others that they are not alone, and that recovery is possible.

I choose to be open about my eating disorder as well. Similarly to Meredith, I strive to be the support that my younger self wished she had. The life I have been able to live in recovery is one I could have never dreamed of while I was in the depths of my disorder, and I am passionate about spreading awareness and being a resource for people who are trying to find that same light.

“I think that if all of us, as a community, were better educated on eating disorders and what they are, then I would have been spared some of the brutal things that happened to me,” says Meredith.

Education on warning signs and helpful ways to support a friend is invaluable knowledge, especially in a high-risk environment like a college campus. Additionally, awareness of what types of comments or remarks might be triggering can help protect vulnerable female athletes from spiraling into disordered behaviors.

When Maddy returned to running after an injury, she recalls being told by her high school coach that she needed to lose weight to run faster.

“That sticks with me,” says Maddy. “I think about it all the time.” Despite having over five years in recovery, Maddy still remembers what her coach told her. Coaches rarely intend to be malicious in their comments, yet their words can have long-lasting consequences for their players. In a system where athletes often look up to their coach and feel pressured to follow their rules, a coach must be extra cautious to consider the implications of their comments.

In addition to coaches, comments from teammates and peers can also influence a student-athlete’s body image. Toward the beginning of her eating disorder, Meredith received an influx of compliments about her body.

“My teammates were complimenting me, saying things like ‘you look so good’ or ‘you look so fit,’” says Meredith. “They were almost fueling my fire a little bit.” Despite being well-intentioned, these compliments validated Meredith’s eating disorder, convincing her the behaviors were okay because people thought she looked good.

Diet culture has normalized complimenting weight loss, instantly praising a person for losing weight without first examining how they did it, and if it was healthy for them. This habit insinuates that a person’s body is less worthy at a larger size, and often encourages the continuation of dangerous behaviors in search of more compliments.

Grace echoes the necessity for further education on eating disorders.

“Anyone of any body weight can have an eating disorder,” she says. “You don’t have to be 90 pounds or 80 pounds to have an eating disorder, and you don’t have to be 300 pounds to have an eating disorder – any body weight from tiny to big can have an eating disorder.”

Leave a comment