Abstract

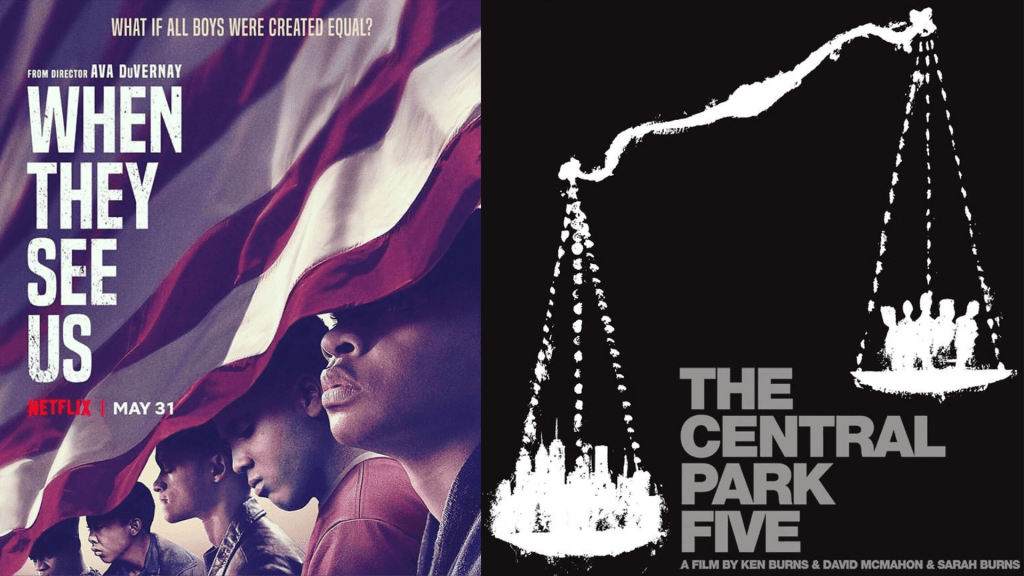

Different forms of media played a key role in telling the story of a jogger that was attacked in Central Park in April 1989. Through examination of early coverage to later depictions, the public can better understand the role that media played in the initial conviction of the five innocent boys, as well as the later exoneration. Newspaper stories used animalistic vocabulary and a presumption of guilt to sway public opinion toward the perceived guilt of the five young boys that were convicted of the crime. The Central Park Five and When They See Us are more recent film depictions of the crime. Through strategies of documentary filmmaking and dramatization of the events, these later drafts of history transition to proving the innocence of these boys to the public.To fully comprehend the nature of the case, the reader must examine each media form as a piece of a greater puzzle.

Key Words: Central Park Jogger, Tabloid Journalism, Wilding, Ken Burns, Ava DuVernay

Introduction

When a privileged, White jogger was attacked in Central Park on April 19, 1989, news organizations jumped to cover it. The stakeout story had journalists crowded outside the hospital room of the jogger, Trisha Meili, begging for any updates on her condition. The result was highly biased newspaper articles focused mainly on praising Meili and dehumanizing the suspects. Using animalistic vocabulary and sensational headlines, these articles affirmed the guilt of the five young teenagers accused of committing the crime. In The Central Park Five, Ken Burns tells the story through a documentary, which uses a fact-based approach to shed light on the media’s role in the wrongful conviction of the boys. In When They See Us, Ava DuVernay directs a dramatization of the case. Her approach strives to evoke an emotional response from viewers. Philosopher and media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously said, “The medium is the message” in his book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964). According to McLuhan, the medium, or platform used to communicate a message, is often more important than the content of the message itself. Tabloid journalism, documentary, and dramatization have very different strategies for how to depict this case to the public. A prominent shift in cultural power is reflected in the media’s portrayal of the Central Park case. This shift is demonstrated by the changing content of media messages, as well as the use of techniques within a given medium to help criminalize or vindicate the five boys.

Newspaper Coverage

Traditional journalistic coverage of the Central Park Jogger case was largely sensational. The stories were mainly produced by White reporters and focused on praising the white jogger while criminalizing the black boys. In an article published just days after the attack, all the suspects are named: “The four are Kevin Richardson, 14, Steve Lopez, 15, Clarence Thomas, 14, and Raymond Santana, 14… The others accused of participating in the rape are Atron McCray, 15, Yusef Salaam, 15, and Kharey Wise, 16” (McKinley, “2 More Youths…”. This newspaper article from The New York Times provided the first and last names of the boys before they were indicted. Researchers in the Criminal Justice Department at Rutgers University also found that these tabloid articles routinely provided photographs, street addresses, apartment complexes, and schools of the boys (Welch et al. 40). Newspaper articles defied the presumption of innocence, a key part of the United States Criminal Justice System, by criminalizing the boys before they had a chance to defend themselves. This legal principle states that a person is innocent unless their guilt is proven beyond a reasonable doubt, commonly referred to as “innocent before proven guilty.” An article published by the Duke School of Law finds that pretrial journalism “tends generally to treat the presumption of innocence as a formality, largely limited to using the word allege” (Entman and Gross 95). The news reporting of crime exhibits a pro-prosecution bias, as demonstrated by the journalistic tendency to dismiss the possibility of an error on the side of the court system and police. In the case of the Central Park Jogger attack, these biased newspaper articles played a key role in shaping how the crime, and especially the suspects, were perceived by the public.

Sensational Reporting: Wilding and Infotainment

Sensational terminology dominated headlines and news articles. This form of journalism, also known as infotainment, involves, “Blurring the conventional lines of so-called factual news reporting and entertainment…whereby news coverage is presented with a greater sense of style intended to not only inform but also entertain viewers” (Welch et al. 38). The most prominent example of sensationalism vocabulary in the coverage of this case was the word “wilding.” The term first came into fruition on the front page of The New York Times, with an article line, “Chief of Detectives Robert Colangelo… said that some of the 20 youths brought in for questioning had told investigators that the crime spree was the product of a pastime called ”wilding” (Pitt 1). In reality, the boys were actually misheard by Colangelo. In the African American Review, researcher Stephen Mexal reveals they were innocently rapping the lyrics to “Wild Thing” by Tone Lóc. (106). With different journalists vying for public attention for their publications, they needed to find ways to get people to choose to read their version of the story. Henceforth, “wilding” caught on among media sources to hook readers into their depictions of the Central Park Jogger case (Welch et al. 38).

Natalie Byfield is a professor of sociology at St. Johns University, who was also a journalist for the Daily News at the time of the Central Park attack. In her reporting of the crime, Byfield observed her editors limit the reporters to just writing about the extent of the jogger’s injuries and the guilt of the boys (60). Byfield reflects, “Media producers did not mind sensationalizing the case and exploiting everyone within reach to make this point” (Byfield 60). Her experience as a journalist reveals the manipulation and framing of the case by the press, a trend that prioritized grabbing the attention of the reader over the implications that the sensational coverage could have on these young boys.

Rapes occurred frequently in New York City in the late 1980s. In fact, police revealed there were 28 reported rapes in the same week that the jogger was attacked (Terry). The prevalence of this form of sexual assault resulted in the word losing much of its power and lure to the press. Wilding, however, was “new, unknown, and menacing” (Welch et al. 38). Countless news organizations integrated the word into their own articles, making it standard practice in the reporting of this particular crime. Using neologisms like “wilding,” as well as other eye-catching vocabularies, demonstrated the newspapers’ prioritization of circulation over the legitimacy of the content they produced.

The prevalence of infotainment in the reporting of the attack helped instill guilt in the boys when realistically very little evidence existed to support the egregious claims in the press. Newspapers were one of the dominant forms of news distribution, hence the public had limited ways to be informed on the true nature of the crime. Lynn Chancer is a Professor of Sociology at Hunter College in NYC. In an issue published by the American Sociological Association, she writes that “the inflammatory animal imagery, Darwinesque in its associations, had the effect of linking a particular group of defendants – the young men who had confessed – to the crime long before they were tried, when they were still supposed to be presumed innocent” (Chancer 39). Chancer affirms the media’s counterproductive role in news coverage, noting that the newspaper articles secured the boys’ convictions before they attended trial to defend themselves. Many local activists, around the area where many of the boys lived, questioned how they could receive a fair trial with all the negative media coverage about the crime (Chancer 39).

Wilding is also rooted in the racist tendencies of the media. Mexal emphasizes the importance of race: “Nonwhite boys had gone wild and maimed a white woman… wilding seemed to radically reimagine the logic of crime, implying an irrational, fundamentally savage eruption of violence without motive” (102). Using this word allowed news organizations to portray black youths as savage, inhumane predators who posed a threat to the community at large. Infotainment drove the coverage of the Central Park Jogger case, and, the literary elements of the story increased popular public beliefs surrounding violence, victimization, and criminal stereotypes (Welch et al. 39). The unfamiliarity and savage nature of wilding also, “served to further distance the crime and the accused from the standards of white ‘civilization’” (Mexal 102).

Underlying Motives of Newspapers

The underlying agenda that this coverage served was supported by increased public concern about violent crime around 1989. Violent crime statistics had risen each year since 1985 which, alongside the city’s failure to hire more police officers, caused public doubt about the cops being able to keep people safe (McKinley, “Killings in ‘89…”). Chancer points out that this growing fear set the stage for a “tough-on-crime” political environment (39). In her dissertation on true crime at Michigan Technological University, Rebecca Frost wrote that crime narratives “work to reassure citizens of their safety and restore order to threatened communities” (Frost 2). In the Central Park case, the newspaper coverage of the crime reassured the public, showing that the criminal had been caught and the police had quickly and flawlessly performed their job. The public trusts newspaper articles, assuming objectivity. Henceforth, inaccurate, agenda-driven news was misinterpreted as true. Frost suggests that public reassurance is rooted in words from an authoritative community member, such as a reporter, regarding the crime and the consequences that the criminal will face (7-8). Additionally, the case acted as a restoration ritual regarding society’s trust in the government’s response to urban violence (Frost 7). Donald Trump, at the time a wealthy New York City resident, also used the attention on the case to push his own racist agenda surrounding minorities in the U.S. Trump published multiple full-page advertisements titled “Bring Back the Death Penalty,” as well as saying, “You better believe that I hate the people who took this girl and raped her brutally” in a news conference in 1989 (Dwyer). Realistically, authorities and political figures were less interested in finding the true perpetrator of the crime, but rather in making an arrest to restore the city’s faith in them.

Television news coverage of this case followed similar trends as print newspapers. In Political Society, Michael Milburn and Anne McGrail discuss the collective shift from objective, factual TV newscasts to a more entertaining, melodramatic form (614). They discuss that the use of drama in television news serves two purposes: “generation of emotional arousal and the use of underlying myths” (Milburn and McGrail 615). TV news frequently utilizes melodramatic forms, or forms of drama that rely on emotional arousal and simplification of characters and plot. (Milburn and McGrail 617). Milburn and McGrail refer to The Moro Morality Play, a book authored by Erica Wagner-Pacifici that discusses melodramatic narrative form. The resolution of these stories is when the clearly defined force of good takes over the clear evil (Milburn and McGrail 617). Everything is black and white, as the gray area breeds uncertainty and is disconcerting for the audience. In melodramatic narratives, “The audience has only one option: to applaud the hero and condemn the villain” (Milburn and McGrail 617). Additionally, news stories normally appeal to a societal myth that the culture can understand and relate to (Milburn and McGrail 617). In the case of the Central Park attack, the media centered around the myth that black men are dangerous criminals. While this is a grossly inaccurate depiction of black males, it was widely believed to be true at the time due to the prominence of racially driven media coverage. Henceforth, the story that a black man had viciously attacked a White woman seemed believable and expected, providing credence to the melodramatic theme that good prevails over evil. Furthermore, this ties into Frost’s point that true crime serves the function of reassuring the public. By reporting on the suspects, TV news assured the public that they were now safe from the threat, while also restoring faith in police and authorities to keep their communities safe. Raising concerns about the boys’ guilt would disrupt the certainty of a melodrama, henceforth news programs had to remain close-minded on their culpability.

Danger Narratives

The racist reporting of crimes is an enduring pattern throughout history, especially through danger narratives. Lindsey Webb, an Associate Professor at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law, defines danger narratives as a genre of crime focused on violence with the intent to purport the danger and criminality of people of color (134). By showcasing people of color, especially black Americans, in this light, dominant White power structures strive “to justify and promote racist practices and institutions” (Webb 134). The media, a largely White field at the time of the Central Park Jogger attack, portrayed the boys as vicious savages. In displaying the boys in such a violent way, journalists likely aimed to justify the racist reporting they were doing on the case. Black men are stereotyped in our society as inherently dangerous and criminal. These misconceptions are fueled by media bias toward framing them in this light. Additionally, this is intensified by the combined gender and race component that, “Violent crimes involving white female victims and black male perpetrators are portrayed as particularly tragic, prompting an outpouring of emotion and outrage” (Welch et al. 38). In the Central Park case, ratings overpowered the ethics of the crime. While news organizations and journalists could fight for the boys’ innocence, and some did, articles praising the jogger were inevitably more profitable and popular. Although the news is meant to be objective and show both sides of a story, the media disregarded the perspectives of the boys in order to boost their profits and push the narrative of white innocence versus Black danger.

Agenda Setting and New York Times Effect

Another relevant phenomenon at this time was The New York Times Effect. In the documentary Page One: Inside The New York Times, James McQuivey, an analyst at Forrester Research, describes this effect as, “if on day one the New York Times ran a piece on a particular story, a political or business issue, on day two the tier two newspapers would all essentially imitate the story” (Braun). At the time of the attack in Central Park, newspapers were the key outlet for reading news. Henceforth, the Times held immense power in its ability to set the agenda and frame stories in a particular light. As a result of this influence, the content they chose to publish about the Central Park Jogger directly influenced the stories that would be reported in the following days by other newspapers. In the week following the attack, the New York Times placed the case on the front page five times, clearly outlining its perceived importance and newsworthiness. Additionally, these articles were largely biased accounts of the case, focused on criminalizing the suspects. The coverage of the Central Park Jogger case undoubtedly followed the New York Times Effect trend, with the media prioritizing the coverage of the crime and unanimously reporting on the guilt of the accused boys.

Documentary Portrayal: The Central Park Five

The Central Park Five was directed by famous documentarian Ken Burns, alongside his daughter Sarah Burns, and her husband David McMahon. The piece, created in 2012, showcases a shift toward displaying the innocence of the five boys, rather than how the media had previously vilified them. Although Burns’ piece is very progressive in its portrayal of the case, his work is inevitably coming from the perspective of a privileged White male. Burns’ documentary fails to elicit the same emotional response and motivation to cause change that DuVernay’s dramatization does, however, this makes sense given Burns, being White, is not directly affected by the daily burdens of racial injustice. The content of the documentary is largely focused on the media coverage at the time of the attack, and Burns appears more interested in what White people did wrong, rather than focusing on the effect the conviction had on the boys. Burns showcases a sense of White liberal guilt in how he tries to be woke and justice-oriented, yet comes across as blaming the media for how they failed to report on the true nature of the crime. The underlying message that Burns conveys touches on the ethical challenges behind the documentary genre and the perceived truth of it. What is a documentary, and what creative liberty does Burns have to implement his own opinion and viewpoints into his piece?

Documentary as a Medium

The documentary label presents Central Park Five as entirely true and objective, but realistically Burns’ personal biases will seep into any film he produces. Jill Godmilow, the producer of multiple documentary films, utilizes her expertise in filmmaking to unpack the true meaning of documentaries. Godmilow thinks the term “documentary” is misleading, as the viewpoint of the producer will inherently be highlighted in what they choose to include. She finds “non-fiction” to be a more accurate label, but not right because it is “built on a concept of something not being something else, implying that because it’s not fiction, it’s true” (Godmilow and Shapiro 80). Henceforth, Godmilow chooses to refer to documentaries as “films of edification,” illuminating the producer’s bias and intention to persuade the viewer’s opinion (Godmilow and Shapiro 81). The attack is a true event, but this method of distributing facts subjects the content to creative liberties that might be taken by Burns.

Author and professor of Film and Media Studies Carl Plantinga discusses the forms and uses of documentaries. He argues that this medium “invariably further interprets the event and involves intentionality,” such as adding music, titles, or voice-over narration (107). Stylistic choices work to assist the audience’s interpretation of the content in the way the director intends them to. Burns utilizes the tools within the medium to assist in his telling of the story. For example, sad music plays in the background while Kevin Richardson cries while recalling being coerced into confessing. The choice to add this music cues emotional sympathy from the audience while watching Richardson’s interview (Burns 17:56-18:32). Although Burns does not include voice-over, the intentionality of his captions is very clear. At the end of the documentary, Burns includes closing remarks. One of the captions reads, “In 2003, a year after their convictions were vacated, THE CENTRAL PARK FIVE filed a civil rights lawsuit against THE CITY OF NEW YORK” (Burns 1:55:53). The words in all-caps are also displayed in a bright white color, whereas the other words are in a less noticeable gray. By making “THE CENTRAL PARK FIVE” and “THE CITY OF NEW YORK” stand out, Burns is likely pointing out the ongoing conflict between both groups. An inability to own one’s mistakes is a theme throughout the documentary, and this caption highlights the tension created by the city official’s reluctance to apologize for their role in the suffering of the boys. The end scene has an upbeat, more positive song in the background. Choosing to end his film in this manner reflects Burns’ hope and optimism for the future of the case.

NYC Officials Try to Sue Burns

New York City officials believed the Central Park Five was a biased depiction of the controversial event, produced to influence the $250 million settlement for the lawsuit filed by the five men, according to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. NYC’s Law Department subpoenaed the project’s production company, Florentine Films, in the fall of 2012, requesting raw video and audio tapes collected throughout the reporting and production process (“Central Park Five Subpoena Quashed…”). The motion to quash the subpoena was granted by Ronald L. Ellis, the United States Magistrate Judge, on the basis that the research behind the film was protected by reporter’s privilege, or a journalist’s limited First Amendment right against being forced to reveal their sources in court (“Central Park Five Subpoena Quashed…”). The ruling for this case was based on an earlier case, Chevron Corp. v. Berlinger, where true-crime filmmaker Joe Berlinger was forced to disclose over 600 hours of footage in 2011 (“Central Park Five Subpoena Quashed…”). However, reporter’s privilege requires reporters to act independently from the subjects of their journalism. The court revealed that Berlinger collaborated with Stephen Donziger, a legal advisor on the oil case his film Crude was based on, henceforth he was not protected under the reporter’s privilege (“Central Park Five Subpoena Quashed…”). Florentine Films, however, established independence in its journalistic process, protecting The Central Park Five under the reporter’s privilege. Additionally, Sarah Burns is a journalist, and she employed many of her skills from that profession in researching the story of the Central Park case. The defendants also failed to show that the information Burns gathered pertained to a significant issue and was unavailable from alternate sources (“Central Park Five Subpoena Quashed…”). Actions taken by New York City officials were attempts at prior restraint, or censorship used to prevent the publication of Burns’ documentary. Despite the charges Burns was accused of, the First Amendment prevailed, with the subpoena squashed and the film released to the public.

Dramatization/Non-Fiction Film: When They See Us

Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us utilizes a dramatization structure to tell the story of the Central Park Five case. This narrative form employs a largely pathos-driven approach to evoke the viewer’s emotions, intending to make them connect more deeply to the content being displayed. The Central Park Jogger attack is a historical event, but having a movie based on a true story does not necessarily constitute its authenticity. Noel Carroll, a leading figure in the philosophy of film and distinguished professor at CUNY Graduate Center, writes, “The film and the writing come labeled, or, as I say, indexed, one way or another, ahead of time” (Carroll, Postmodernist Skepticism 169). The non-fiction genre implies an objective, fully true depiction for DuVernay’s film. However, objectivity is impossible to achieve when a producer is crafting the film through their own set of beliefs and ideas.

Objectivity in Non-Fiction Films

Carroll delves further into the process of non-fiction events being produced into films. Intentional or not, he acknowledges that personal interests, viewpoints, and biases will inherently enmesh themselves within a director’s work. Carroll points out, “Objectivity is impossible if only because of the medium itself due to framing, focusing, editing” (Carroll, From Real to Reel 5). However, Carroll does not believe these shortcomings discredit the authenticity and worthiness of non-fiction films, so long as the producers are open to criticism and evaluation of their work based on the set of objectivity standards (Carroll, From Real to Reel 16-17). Filmmakers are also normally transparent about how their point of view might impact the content they produce, presenting non-fiction films as their subjective reality, or their vision of reality (Carroll, From Real to Reel 7).

Okaka Opio Dokotum, associate professor of literature and film at Lira University in Uganda, points out the role that Hollywood has in fictionalizing elements of movies labeled as “based on a true story” (148). The production techniques of staging films in contemporary contexts often interfere with a true historical recount. Dokotum synthesizes, “Films about the past become in many ways films about the present” (152). When They See Us highlights Dokotum’s theory, with DuVernay combating social issues in 2019 through the story of the Central Park boys. By connecting this case to current injustices in America, specifically the Black Lives Matter movement, Duvernay is able to shed light on the traumas and injustices that were endured by these boys at a time when black voices were largely suppressed by the media. For too long, the boys were not seen, their voices suppressed by dominant White figures who used the case to push racist agendas. However, the present-day movement to highlight racial inequality in our society provided a platform for DuVernay to finally make them seen, as referenced in the title When They See Us. Through her Netflix series, Duvernay was able to pursue a new agenda: one centered on freeing the boys, not criminalizing them. Alissa Wilkinson, a film critic who writes for Vox, discusses DuVernay’s success at using the case to highlight the presence of racism in the present day. She notes that what DuVernay’s series does is, “try to snatch the image collectively created by a country’s fevered imagination back from history and recreate it as a story about five men and their families” (Wilkinson).

Dramatization as a Medium

Through dramatizing this case, DuVernay humanizes the boys and illustrates the ways in which the flawed institutions in the United States led to their wrongful convictions. Although she focuses on a single case, her depiction of the police and the public’s analogous responses illuminates the bigger-picture issue: the media’s racist portrayals of black people shape public opinion over time. This ideology is supported by cultivation theory, a term coined by George Gerbner, a professor in the field of communications. The theory states that repeated exposure to ideas on media platforms can shape the attitudes of the viewer over an extended period of time. The authorities and public blindly assuming the boys were guilty due to their race showcases the deeply rooted racial prejudices in our country. DuVernay’s decision to focus on this one case is effective in how the audience feels emotionally connected to the characters being hurt, while her depiction of the way this case was handled demonstrates the role that stereotypes play in the biased assumption of guilt and wrongful convictions of Black Americans.

Although some might argue that DuVernay’s series is a biased representation of the case, rather, her piece is defying historical trends to provide a new lens through which to understand the case. While non-fiction films inherently contain bias, Carroll discerns that the telling of history itself is subjective, with dominant perspectives constantly being emphasized in the recollection of events. Winston Churchill famously said, “History is written by the victors.” Churchill was referencing the interpretation and biases of dominant societal forces dictating how history is told. Similarly to the personal perspectives of film directors, history is also told through the lens of a human with a unique set of beliefs. A skewed version of history was told until the boys were exonerated, henceforth DuVernay’s one-sided depiction is more so laying out facts that were missed during the first media cycle in 1989. Carroll encapsulates the debate over the validity of nonfiction productions, stating that “commentators who conclude that the nonfiction film is subjective intend their remarks as a mere gloss on the notion that everything is subjective” (Carroll, From Real to Reel 9). Everything is tainted by subjectivity; films are no exception. Discrediting a film for including a director’s point of view is similar to shunning a historical account for containing biases of the author.

In terms of creative liberty, Carroll believes that producers are allowed to incorporate their own stylistic components into the piece. He writes that “a nonfiction filmmaker may be as artistic as he or she chooses as long as the processes of aesthetic elaboration do not interfere with the genre’s commitment to the appropriate standards of research, exposition and argument” (Carroll, From Real to Reel 17). A director has the license to use cinematography to enhance the telling of the story, but the events can not be falsified or reinvented for the sole purpose of enhanced aesthetic effect. In historical fiction, the director has free range of the plot and storyline. The nonfiction genre differs in the rigidity that is placed on the facts and accuracy of the real-life events being portrayed (Carroll, From Real to Reel 17). The complex task in When They See Us is determining if DuVernay’s creative choices in the production of her film interfere with telling the true story of the Central Park case. A loophole for dissecting the truth is the lack of concrete evidence around more minor, minuscule details surrounding this story. For example, at the beginning of episode three, Raymond Santana’s grandmother is shown at her birthday party, seemingly too distraught from her grandson’s conviction to celebrate or experience joy. Although this scene is heart-wrenching, is it historically accurate? And if DuVernay included the scene as a theoretical depiction, does that detract from the true nature of the story?

In a piece in the Wall Street Journal, Linda Fairstein, the district attorney who covered this case, combats her portrayal in DuVernay’s series. She defends her actions, saying she was not “unethically engineering the police investigation and making racist remarks,” nor did she run the investigation and arrive before dawn on April 20 (Fairstein). Fairstein also points out other discrepancies between her actions and what was portrayed in the film. In response to her role in When They See Us, Fairenstein states, “Ms. DuVernay ignored so much of the truth … and that her film includes so many falsehoods is nonetheless an outrage” (Fairstein). Fairstein’s pushback raises important questions surrounding the truth of the film. Deanna Paul, a journalist at the Washington Post, points out the tremendous success that When They See Us has had, but also expresses concern with how parts of the case are missing in DuVernay’s portrayal (Paul). She mentions an “unspoken tension” between depicting a story artfully versus accurately, as well as how DuVernay took numerous liberties in her retelling of the events that took place in Central Park that night (Paul). Sarah Burns spoke about DuVernay’s film during an interview with AM New York. She admitted that there are “little points where things diverge from the timeline, but I understand you take some artistic license when telling a story” (Paul). Burns mentions conversations between law enforcement officers and muddled verdicts as two falsities in DuVernay’s piece. Cathy Young, a writer at The Bulwark, elaborates on these potential problems surrounding DuVernay’s portrayal of the case. Young points out the minimization of the crime spree that took place in Central Park on April 19. She also suggests the influence of gender on the public’s opinion. People who suspected the innocence of the boys were afraid to come across as “anti-woman,” as defending the accused rapist was seen as opposing the feminist movement of the time (Young). The movements against sexism and racism clashed, forcing people to pick a side. In rape cases, especially, the public tends to side with the victim.

To fully understand the dynamics surrounding the Central Park case, the public must engage with each of the media’s portrayals of it. To grasp the shortcomings and racist roots of the early coverage, viewers must analyze the initial newspaper and broadcast coverage of the attack. Considered the first draft of history, these sensational stories used animalistic vocabulary and a presumption of guilt to convince the public of the boys’ guilt. The more recent interpretations see things differently. In The Central Park Five, Burns creates a meaningful, fact-based transition from the earlier paintings of the case to the newfound innocence of the boys. The most recent depiction, When They See Us, strives to evoke an empathetic response from viewers by recreating the events surrounding the wrongful conviction, imprisonment, and exoneration of the five boys. To fully comprehend the nature of the case, without being influenced by any single bias, the reader must digest each media form as a piece of a greater puzzle. The varying perspectives and messages build upon one another to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its many complexities. To properly gauge the relevance of hearing suppressed voices, the public must also understand the historical context that alienated those voices in the first place.

Works Cited

Braun Josh et al. directors. Page One: Inside the New York Times. Magnolia Pictures; Distributed by Magnolia Home Entertainment 2011.

Byfield, Natalie, Savage Portrayals: Race, Media and the Central Park Jogger Story. Temple University Press, 2014. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt6kc

Carroll, Noël. “Nonfiction Film and Postmodernist Skepticism.” Engaging the Moving Image, Yale University Press, 2003, pp. 165–92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1nps8x.12.

Carroll, Noël, ‘Nonfiction Film and Postmodernist Skepticism’, Engaging the Moving Image (New Haven, CT, 2003; online edn, Yale Scholarship Online, 31 Oct. 2013).

“‘Central Park Five’ Subpoena Quashed after Filmmakers Prove Their Independence.” The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, www.rcfp.org/journals/central-park-five-subpoena/.

Chancer, Lynn. “Before and after the Central Park Jogger: When Legal Cases Become Social Causes.” Contexts, vol. 4, no. 3, 2005, pp. 38–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41800927.

Dokotum, Okaka Opio. “This Is ‘a True Story!’” Hollywood and Africa: Recycling the “Dark Continent” Myth from 1908-2020, NISC (Pty) Ltd, 2020, pp. 147–72. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvxcrxs1.13.

DuVernay, Ava, dir. When They See Us. NetFlix, 2019.

Dwyer, Jim. “The True Story of How a City in Fear Brutalized the Central Park Five.” The New York Times, 30 May 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/05/30/arts/television/when-they-see-us-real-story.html.

Entman, Robert M., and Kimberly A. Gross. “Race to Judgment: Stereotyping Media and Criminal Defendants.” Law and Contemporary Problems, vol. 71, no. 4, 2008, pp. 93–133. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654685.

Fairstein, Linda. “Opinion | Netflix’s False Story of the Central Park Five.” The Wall Street Journal, 11 June 2019, www.wsj.com/articles/netflixs-false-story-of-the-central-park-five-11560207823.

Frost, Rebecca, “Identity and Ritual: The American Consumption of True Crime,” Open Access Dissertation, Michigan Technological University, 2015. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/17

Godmilow, Jill, and Ann-Louise Shapiro. “How Real Is the Reality in Documentary Film?” History and Theory, vol. 36, no. 4, 1997, pp. 80–101. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2505576.

Pitt, David E. “Jogger’s Attackers Terrorized at Least 9 in 2 Hours.” The New York Times, 22 April 1989, p. 1, 30.

Terry, Don. “In Week of Infamous Rape, 28 Other Victims Suffer.” The New York Times, 29 May 1989, p. 25.

McKinley, James C. “Killings in ’89 Set a Record In New York.” The New York Times. 31 Mar. 1990, p. 27.

McKinley, James C. “2 More Youths Held in Attacks in Central Park.” The New York Times, 23 Apr. 1989, p. 32.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. [1st ed.] New York, McGraw-Hill, 1964.

Mexal, Stephen J. “The Roots of ‘Wilding’: Black Literary Naturalism, the Language of Wilderness, and Hip Hop in the Central Park Jogger Rape.” African American Review, vol. 46, no. 1, 2013, pp. 101–15. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23783604.

Milburn, Michael A., and Anne B. McGrail. “The Dramatic Presentation of News and Its Effects on Cognitive Complexity.” Political Psychology, vol. 13, no. 4, 1992, pp. 613–32. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3791493. Accessed 13 May 2023.

Paul, Deanna. “‘When They See Us’ Tells the Important Story of the Central Park Five. Here’s What It Leaves Out.” The Washington Post, 29 June 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/06/29/when-they-see-us-tells-important-story-central-park-five-heres-what-it-leaves-out/.

Plantinga, Carl. “What a Documentary Is, After All.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol. 63, no. 2, 2005, pp. 105–17. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3700465.

United States District Court: Southern District of New York. Florentine Films v. New York City Law Department, 03 Civ. 9685 (DAB) (RLE). 2012.

Welch, Michael, et al. “Youth Violence and Race in the Media: The Emergence of ‘Wilding’ as an Invention of the Press.” Race, Gender & Class, vol. 11, no. 2, 2004, pp. 36–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41675123.

Webb, Lindsey. “True Crime and Danger Narratives: Reflections on Stories of Violence, Race, and (in)Justice.” The Journal of Gender, Race, and Justice, vol. 24, no. 1, 2021. ProQuest, http://stlawu.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/true-crime-danger-narratives-reflections-on/docview/2682503779/se-2.

White, Hayden. “The Question of Narrative in Contemporary Historical Theory.” History and Theory, vol. 23, no. 1, 1984, pp. 1–33. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2504969.

Wilkinson, Alissa. “Ava DuVernay Uses Real History to Damn the Present in Netflix’s When They See Us.” Vox, 2 June 2019, www.vox.com/culture/2019/6/2/18646523/when-they-see-us-donald-trump-central-park-five-netflix-ava-duvernay.

Young, Cathy. “The Problem with ‘When They See Us.’” The Bulwark, 24 June 2019, www.thebulwark.com/the-problem-with-when-they-see-us/.

Leave a comment